Why do we feel pressured to fall in line?

An essay about lessons learned from lines and lemonade.

Welcome to the fifth issue of Great Stuff! In this issue, I’ll be talking about a surprisingly common phenomenon: the pressure to fall in line with those around us.

I was motivated to write about this because of something I observed last weekend. I visited a farmers market with a couple of friends, and we found ourselves in front of a lemonade stand selling all kinds of flavors. My friends both went with plain lemonade. Even though the stand was selling some pretty interesting flavors, I somehow felt pressured to go the traditional route as well. When I got home, I was struck by the absurdity of this feeling. There was no time constraint, no possibility of judgment, no real reason not to go with something else. It was just lemonade. Yet there was something at the back of my head that said, “Don’t be a special little snowflake! Get what everyone else is getting!”

I was sure this feeling was fairly common, so I decided to do a little more research. What I found was pretty insane:

The Asch conformity experiment

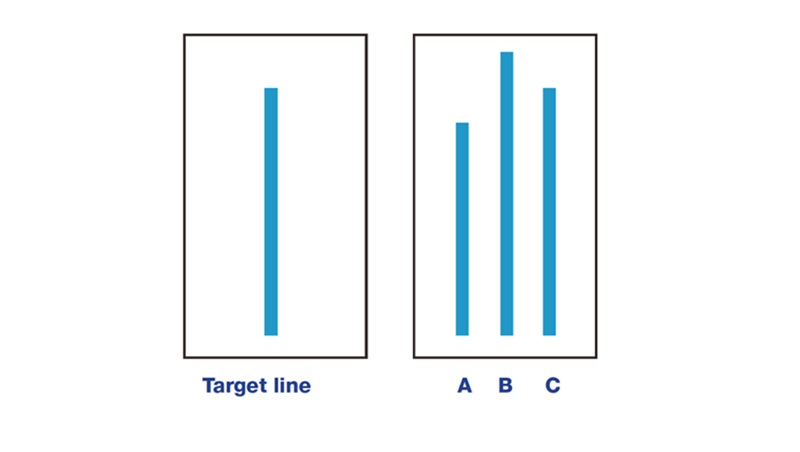

In the mid-20th century, a guy named Solomon Asch developed an experiment to figure out how strongly humans conform to the group they’re in. I’ll spare you the nitty gritty of the experiment, and instead ask you to try it out for yourself. The image on the left depicts a “target line” of a certain length. I want you to figure out which of the lines on the right matches it in length (A, B, or C):

It should be obvious to you that the answer is C. Here’s the catch, though: In the actual experiment, there was only a single “real” participant in the room. Everyone else was an actor who would pick the wrong option. This was what made the experiment so clever. Asch was trying to study how frequently people would go against their own inclinations to align themselves with the majority.

His findings were crazy. Without the actors, only ~1% ever got the answer wrong. With the actors, though, this jumped up to 75%. Also, 5% of people conformed every single time time they were tested, while 25% of people never conformed. That is to say, there were “sheep” and “rebel” subgroups.

Why should you care?

“Alright,” you’re thinking, “this lemonade and lines stuff is all fine and dandy, but what has this got to do with me?” Ok, bear with me here. You may have heard a common saying about confidence: If you speak up in class, you’ll find it easier to give a presentation; if you give a presentation, you might find it easier to speak on a stage; and so on. But what we don’t realize is that the converse applies as well. Left unchecked, little issues bubble up—this is the basis of the butterfly effect.

My thesis here is that our tendency to fall in line can snowball as well. If we get too used to it in the smallest of decisions, then we become less likely to push back in the more consequential ones. I don’t think I have to convince you that the ability to think for yourself is important. At the societal level, groupthink can cause all kinds of problems; political polarization is a particularly pernicious example. At the individual level, it can mean losing important opportunities and, well, becoming wimpy.

But most importantly, by conforming, you prevent yourself from saying anything new and important.

Of course, there are situations where it’s convenient to conform—after all, there’s got to be some evolutionary reason humans conform so strongly. If there’s a time constraint, for instance, going with what everyone else wants usually reduces friction. But being more conscious of this is important to ensure we don’t get used to it.

I’ve spent some time thinking about how to think more independently. Since the lemonade incident, I’ve encountered some fairly interesting ideas about different kinds of conformity. By far the best among these is Paul Graham’s essay, “How to Think for Yourself.” My key takeaways were as follows:

-

If the people around you are independent-minded, you’ll frequently find yourself surprised by their beliefs.

-

If not knowing other people’s opinions makes you uncomfortable, it might be because you’re defining your own beliefs based on theirs. It might also mean they’re suppressing your ability to think for yourself by expecting you to follow them.

-

By far the best way to think for yourself is to avoid spending all your time with the same kinds of people. This way, you won’t have a consistent group to conform to.

-

Avoid ideologies, because good ideas don’t come bundled in neat little packages.

I hope you enjoyed this issue. Here’s a “playlist” of content you might enjoy after this:

-

An Overcoming Bias post, which suggests an economic model for judging conformity. Not super relevant, but I found it interesting nonetheless.

-

A Mind Field episode about conformity, by Michael Stevens of Vsauce. This is incredibly fun. You get to watch people laugh at jokes they don’t find funny simply because they want to conform.

-

Paul Graham’s essay on How to Think for Yourself.

See you next time!

This is cross-posted from my newsletter, Great Stuff. If you liked it, be sure to subscribe!