Analyzing dependencies of JavaScript snippets

Where I befriend Babel to parse out identifiers referenced in code.

I’m working on a way to build apps using a spreadsheet-like system called Smoothie. In place of formulas, Smoothie allows you to write arbitrary JavaScript snippets that can reference other cells.

To run a snippet, Smoothie wraps it in a function and calls the function. But that’s not enough. Consider this snippet:

return A1 + B2 * 5If we just wrap this in a function and call it, we’ll get an error:

;(function () {

return A1 + B2 * 5

})()ReferenceError: A1 is not definedYou can probably see that A1 and B2 need to be in scope to evaluate this expression. We can make them available by passing them as arguments:

;(function (A1, B2) {

return A1 + B2 * 5

})(A1, B2)It’s clear to us that A1 and B2 need to be passed, but how can we program the computer to figure that out for us? The problem we’re faced with is parsing out the dependencies of a snippet of code. Let’s dig into the details.

Understanding the problem

On a cursory look, it seems like a simple approach could work: split on spaces and collect the parts that look like identifiers, perhaps using a regex. But this kind of approach breaks down on complex code. Consider this multiline snippet that takes parses B1 into a number, adds A1, and returns a status message:

const sum = (a, b) => Promise.resolve(a + b)

let B2

{

const B1 = parseInt(B1.value)

B2 = await sum(B1, A1)

}

return `${B2} is the sum of ${B1} and ${A1}.`From this example, it should be clear that splitting on spaces won’t work. There's too much going on syntactically.

In addition, the meaning of the program also complicates things:

B1is read on the RHS of line 4 and and then bound on the LHS.B2is bound without first being read, "shadowing" the cellB2, so even though it looks like a dependency, it isn’t.- There are references to globals like

PromiseandparseInt, which are irrelevant for this use case.1

Accounting for these nuances, the dependencies of this snippet are B1 and A1. Our approach needs to be able to deal with this kind of complexity.

A better approach

It’s literally impossible to use a pattern-based approach to analyze a language as complex as JavaScript, so you’d certainly go crazy trying.2 Instead, we can use a library to parse the snippet into an Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) and traverse it to find identifiers. The Babel parser is the most popular way to do AST traversals of this kind. (There’s also acorn, but its included types are incomplete, and that seems unlikely to change.)

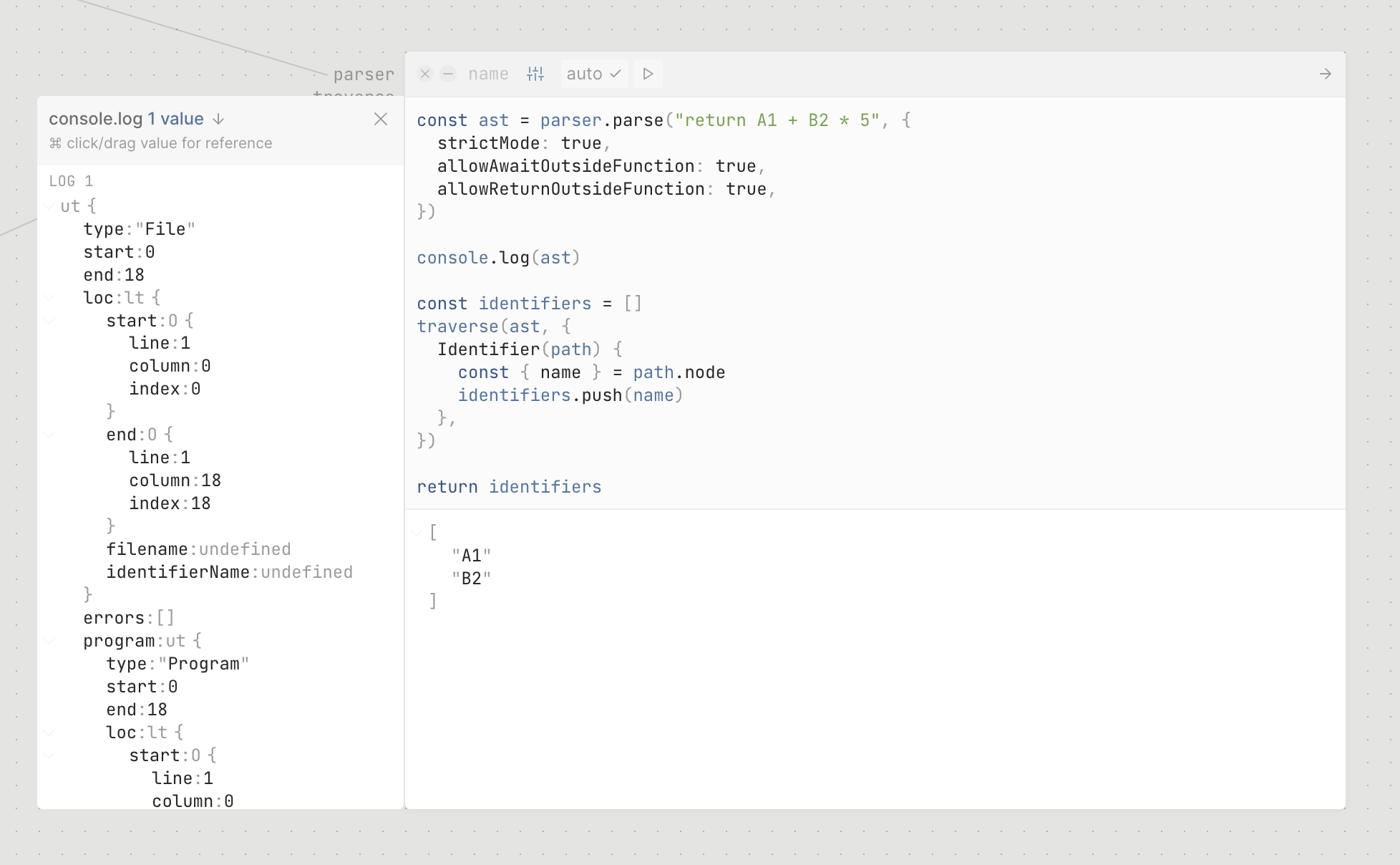

Let’s try and use the Babel parser to reliably figure out what identifiers our snippet needs:

import { parse } from "@babel/parser"

import traverse from "@babel/traverse"

const ast = parse("return A1 + B2 * 5", {

strictMode: true,

allowAwaitOutsideFunction: true,

allowReturnOutsideFunction: true,

})

const identifiers = []

traverse(ast, {

Identifier(path) {

const { name } = path.node

identifiers.push(name)

},

})

console.log(identifiers)This simple script outputs ["A1", "B2"]. Neat!

Unfortunately, this implementation is still flawed. Naively collecting all identifiers includes irrelevant ones, such as:

- Properties of objects, due to member expressions like

D4.value; bothD4andvalueare included. - Targets of variable declarations, like

xinconst x = 5.

Fortunately, the Babel handbook tells us there’s a generic way to deal with all of these cases in one go. Just add a check for path.isReferencedIdentifier():

traverse(ast, {

Identifier(path) {

const { name } = path.node

if (!path.isReferencedIdentifier()) {

return

}

identifiers.push(name)

},

})This accounts for those edge cases.

Because I also want to ignore globals like Promise and limit dependencies to A1-style cell references, I added a few more checks. Here’s what I ended up with:

import { parse } from "@babel/parser"

import traverse from "@babel/traverse"

import { es2020 } from "globals"

function isReference(str: string): boolean {

return /^[A-Z]\d+$/.test(str)

}

/**

* Parse a string of code to find its dependencies.

* @param str A string of code.

* @returns A list of cell names that the code depends on.

*/

export default function parseDeps(str: string): string[] {

let ast

try {

ast = parse(str, {

strictMode: true,

allowAwaitOutsideFunction: true,

plugins: ["estree"],

sourceType: "script",

})

} catch {

return []

}

// Collect dependencies by traversing the AST.

const identifiers: string[] = []

traverse(ast, {

Identifier(path) {

const { name } = path.node

if (!path.isReferencedIdentifier()) {

return

}

if (Object.hasOwn(es2020, name)) {

// Ignore predefined globals.

return

}

identifiers.push(name)

},

})

const dependencies = identifiers

.filter((ident, idx) => identifiers.indexOf(ident) === idx) // Deduplicate.

.filter(isReference) // Filter for cell references.

return dependencies

}This code uses es2020 from the globals package to ignore global identifiers.

Dealing with assignments

Recall the complex example from earlier:

const sum = (a, b) => Promise.resolve(a + b)

let B2

{

const B1 = parseInt(B1.value)

B2 = await sum(B1, A1)

}

return `${B2} is the sum of ${B1} and ${A1}.`Running my code on this example returns ["B1", "A1", "B2"]. We’ve mostly solved the problem, but we’re still left with B2, which is bound before its use.

Fortunately, we can use path.scope.hasBinding(name) to figure out if an identifier is bound in the current scope. We can use this to ignore B2:

if (path.scope.hasBinding(name)) {

// Ignore declared variables.

return

}With this final addition, the output for our example becomes ["B1", "A1"].

In practice, it’s probably bad for users to shadow cell references. Shadowing can result in hard-to-debug issues, which is why ESLint has a rule disallowing it. But it’s still good to account for it in our analyzer.