I wrote a Brainfuck to Go compiler

And it taught me about writing actually useful compilers.

In 2017, I wrote Walnut, a toy compiler that converts Brainfuck code to its equivalent Go program. In this post, I describe how I built Walnut and how the process generalizes to writing useful compilers.

Brainfuck is an “esoteric programming language”—not meant to write software, but to show how small a programming language can be. There are only 8 possible commands you can use (-+.,[]><). This minimalism makes it trivial to write a compiler, since the set of possible inputs and outputs is tiny.

How Brainfuck works

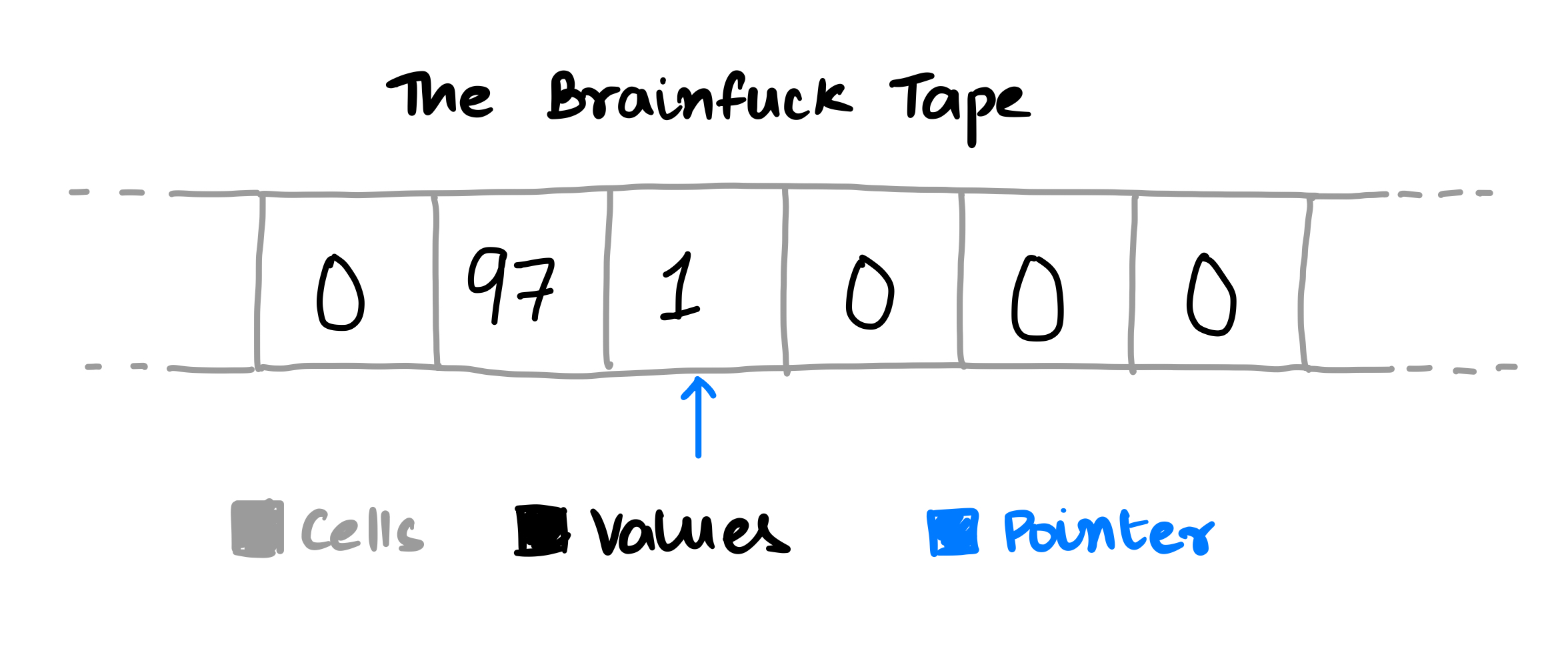

A Brainfuck program operates on a 30,000 cell “data tape” with a pointer. Each cell can contain either zero or a positive integer:

The Brainfuck commands each manipulate either the current cell or the pointer, and [ and ] together enable looping:

| Command | Effect |

|---|---|

- |

Subtract 1 from the current cell |

+ |

Add 1 to the current cell |

, |

Accept an ASCII character as input and store its value in the current cell |

. |

Output the current cell interpreted in ASCII |

< |

Move the pointer left on the tape |

> |

Move the pointer right on the tape |

[ |

If the current cell is nonzero, execute the commands until the corresponding ]. Otherwise skip to the command after the corresponding ]. |

] |

Go back to the corresponding [. |

Let’s see a hello world example. If you want to output HW, you push the ASCII values of H and W, which are 72 and 87, onto the data tape and print them:

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++.

+++++++++++++++.This can be compressed with a loop:

# Store a loop counter initialized at 8 in cell 0

# Then use a loop to add 9 to cell 1 8 times

++++++++[>+++++++++<-]>.

# Add 15 to that

+++++++++++++++.And voila: The program outputs HW as expected. Not very impressive; this kind of programming might seem like it lends itself only to trivial programs. But get ready to have your mind blown. Here’s a Mandelbrot fractal viewer written in Brainfuck and compiled using Walnut:[1]

How awesome is that? One of the fun things about writing a compiler is that you get to marvel at the incredibly complex things it enables. So let’s see how the Walnut compiler works.

The Walnut compiler has two “phases”: parsing the source code into a meaningful data structure and generating Go code from this data structure. To write a Brainfuck compiler, you don’t actually need to do any parsing; you can generate Go directly from the Brainfuck source. But I learned so much about parsing by overengineering anyway. In the following two sections, I talk about how these two phases are implemented.

Parsing the source

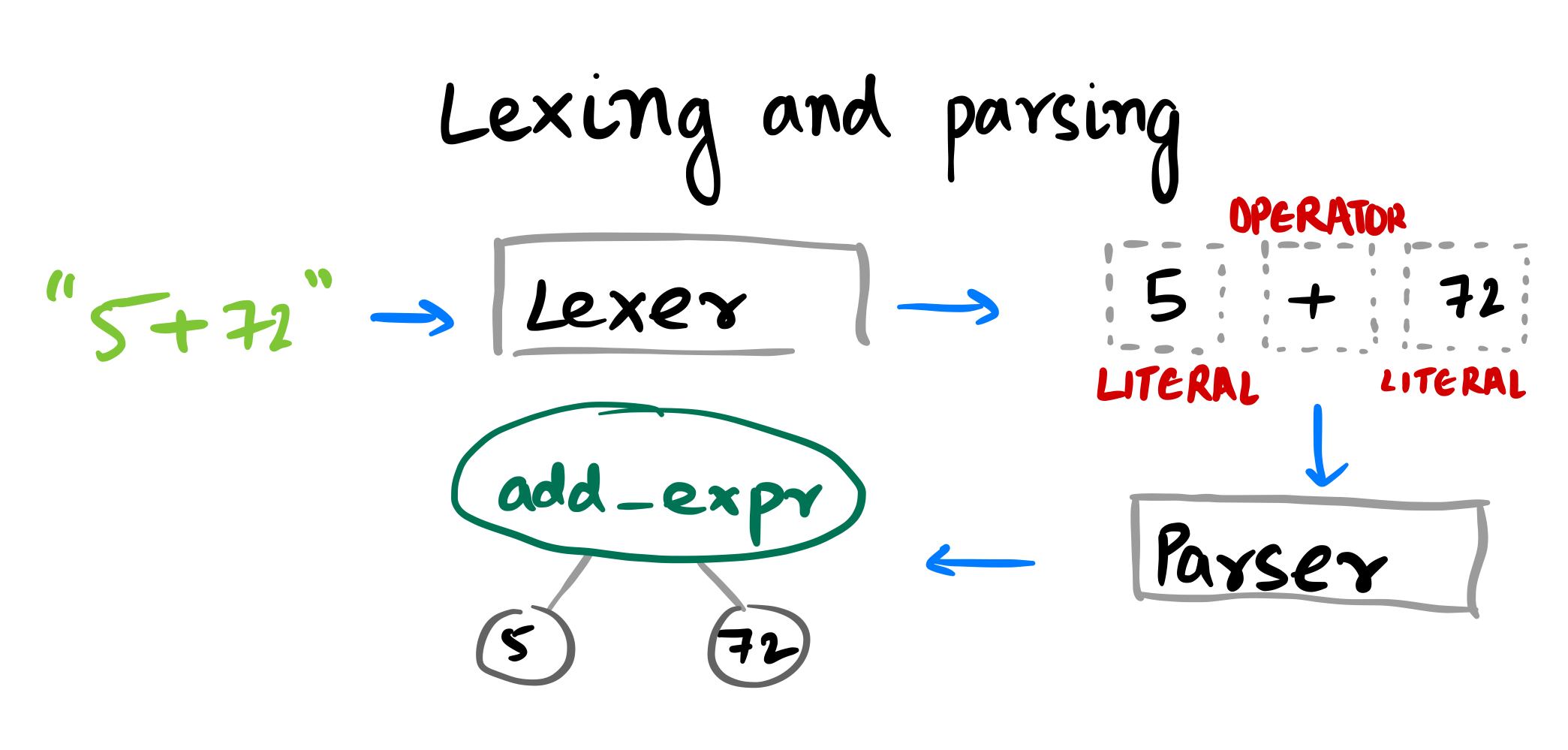

Typically, a compiler will first lex the source code into an array of “tokens” and then parse this array into an “abstract syntax tree”:

However, because of Brainfuck’s minimalism, its AST resembles an array. So we don’t need a separate parser. Our lexer can do the parsing for us. To write this lexer, I used a method described in Rob Pike’s Lexical Scanning in Go. (People will often use a parser generator like yacc to generate a parser from a formal specification of the language called a “grammar”, but this is overkill for Brainfuck.)

I suggest looking at Rob Pike’s lexer talk since it’s fairly accessible, but here’s a brief description.

We start with a bunch of helper functions. Each helper lexes a single type of token at the beginning of the input. For example, the lexIdentifier helper might take the string x := 5 and return x. Crucially, each of these helpers chomps off the portion of the string it is able to lex; lexIdentifier would chomp the x, leaving := 5 for other helpers to lex. (The whitespace is trivial to handle, so I will mostly ignore it.)

Now that we have these ingredients, we recognize that we can treat our lexer as a machine that pushes the input through a series of helpers. Each helper lexes out a token from the beginning of the string, chomps out what it has lexed, and passes control to the helper that can lex the next portion of the string. So the lexIdentifier helper we encountered earlier might pass control to the lexOperator helper, which might pass control to yet another helper. We repeat until we hit the end of the input.

This logic is implemented in the Walnut file parser.go. (Again, keep in mind that this parser is really just a lexer in disguise.) To see what the helpers look like for Brainfuck, here’s the code that lexes loops:

func parseLoop(p *parser) stateFn {

begin := p.ptr

c := p.next()

var l, r int

for {

if c == '[' {

l++

} else if c == ']' {

r++

}

if l-r == -1 {

break

}

if p.peek() == eof {

return p.errorf("unclosed loop")

}

c = p.next()

}

end := p.ptr

p.emit(loopStart{})

for i := range parse(p.tape[begin+1 : end]) {

p.emit(i)

}

p.emit(loopEnd{})

p.next()

return parseDefault

}This code finds the corresponding loop end (]) for the loop start ([) and recursively parses the contents of the loop.

If you follow the logic above to build a lexer, you’ll run into a problem: What helper should our lexer call first, at the very start of the source code? To figure this out, note how the parseLoop helper returns parseDefault. This is a helper that we use when it’s not clear what type of token will come next. Since we don’t know what we’ll see after the loop, we simply return control to parseDefault. Other Go lexers follow the same strategy. In the lexer for the html/template package, which provides HTML templating, the default helper is lexPlainText, which lexes everything until the first {{. (A template looks like Hello, {{ name }} where name gets replaced with the name you pass in when you’re compiling the template.)

Now that we’ve got a lexer working, can we optimize the AST somehow? Turns out that this is pretty easy. For instance, consecutive commands that act on the pointer or cell can be collapsed: >>>>< becomes >>>, and -+-+-+- becomes -. This is called constant folding. Further, Brainfuck has common idioms like [-], which zeroes the current cell by repeatedly subtracting 1 until the loop breaks. How do we implement these optimizations? A typical parser does this by looking at the AST and replacing nodes with equivalent optimized alternatives. Walnut does this using run-length encoding: rather than putting >>>> in the AST, it puts 4>. For common idioms, Walnut simply substitutes them for an equivalent AST node that does the required operation directly.

Generating Go code

This is the simplest step. We simply substitute the corresponding Go code for each node in our AST into this Go template:

func main() {

var (

mem [{{.Memsize}}]int

ptr int = {{.Ptr}}

err error

n int

)

{{.Code}}

// Ensure go doesn't complain about unused imports or variables

func(a ...interface{}) {

_ = fmt.Sprint()

}(n, err)

}For example, the command + gets replaced with mem[ptr] += 1, < with ptr -= 1, and so on. This is how you’d do it even if you were trying to compile to assembly. (This would make it a true compiler.) The only difference would be that you’d have to be more clever about loops. Since Go has built-in for loops, we just convert [<...>] to for mem[ptr] != 0 { <...> }. But assembly doesn’t have those—instead, it has “jumps”. So for each loop, we’d have a slightly more complicated template. Perhaps something like this:

loop_k456ksxf:

beqz x0 return_point

<...>

j loop_k456ksxfParser generators, LLVM, and beyond

You don’t have to actually write your own parser. If you define the syntax rules of your language in a notation like Extended Backus Naur Form (EBNF), you can just use a parser generator. A parser generator takes the rules and generates a program capable of parsing strings that follow them. For instance, here’s the rule for Python’s assignment statements:

assignment:

| NAME ':' expression ['=' annotated_rhs ]

| ('(' single_target ')'

| single_subscript_attribute_target) ':' expression ['=' annotated_rhs ]

| (star_targets '=' )+ (yield_expr | star_expressions) !'=' [TYPE_COMMENT]

| single_target augassign ~ (yield_expr | star_expressions)The entire Python grammar is available here. It’s great inspiration for specifying your own languages.

There’s plenty of tooling available for code generation too. Modern compilers frequently use a toolchain called LLVM behind the scenes. For example, clang, the default macOS C compiler, uses LLVM. What does LLVM do? Well, consider what happens when you want to compile to assembly. If your hand-rolled compiler generates x86_64 assembly, then your programs won’t run on an ARM machine like an M1 Mac. So you’ll have to go and manually implement another output format for your compiler.[2] What LLVM enables you to do is simply write a “front end” that compiles your language down to what it calls an “Intermediate Representation” (IR). Then, LLVM takes care of compiling the IR to any number of instruction sets, from ARM and MIPS to x86_64 and WebAssembly.

Most languages that people use, from JavaScript to Python to Ruby, are written in C or C-derivatives like C++. However, many people swear by writing their compilers in functional languages like Haskell and OCaml. There’s loads of recursion when you’re working with ASTs, and functional languages make that part significantly easier. Plus they’re fast, safe, and expressive. As a byproduct, Haskell and OCaml also have very mature ecosystems for this kind of thing.

If you enjoyed this intro to the Walnut compiler, I’d suggest reading the Dragon book, which is one of the classic compiler textbooks. There’s also Writing a C Compiler by Nora Sandler, which Hacker News people seem to like. Finally, you can access the Walnut source code on GitHub.

This was written by Erik Bosman. It’s not written directly in Brainfuck; Bosman created snippets of commands that accomplished high-level tasks and stitched them together. Abstraction abstraction abstraction! ↩︎

Actually, this isn’t strictly true; you could use tools that convert from one instruction set to another. But this will probably be more trouble than it’s worth. ↩︎